Viva Vivian: the best Golden Age series you haven't read

Published on: 15th August 2022

I started reading detective fiction very young, in the early 1970s when, other than what was available at home (Conan Doyle, Christie, Sayers), I was limited by what turned up second-hand for coppers. I knew no-one who shared my interest so mostly read the bigger names, plus a few whose spot in the limelight was pale but across whom I somehow stumbled. For instance, I can’t remember how I discovered Patricia Wentworth’s Miss Silver books but those became as canonical to me as Holmes, Poirot or Wimsey, though I knew no-one else who’d heard of them until relatively recently.

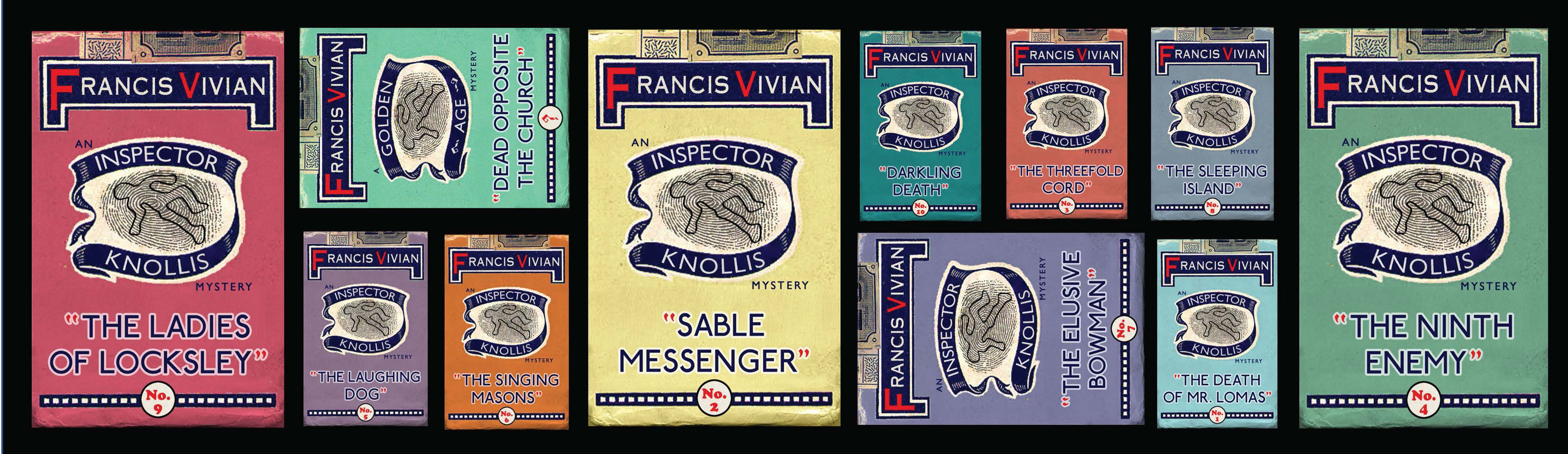

While the Internet may not be an entirely unmixed blessing, it has become a wonderful way of discovering new (to me) books and authors. The recent proliferation of reprints of mysteries from the, ahem, “Golden Age” (broadly the period between the two World Wars, though many of my favourites are from the 1940s and 1950s) has been a source of wonder – how did I not know so many of these books? The British Library Crime Classics series is terrific and has introduced me to E.C.R. Lorac, George Bellairs and many more, but plays if not always fast then often a little loose with chronology and any bigger picture. The Dean Street Press, on the other hand, has largely, and admirably, focussed on series, making it possible to follow the adventures of newly-discovered favourites such as Brian Flynn’s Anthony Bathurst and Christopher Bush’s Ludovic Travers in batches.

This is important. While clearly there are many classic standalone mysteries, would Holmes, Poirot and Wimsey hold their places in British – nay, world – culture if we had only The Hound of the Baskervilles (Holmes’s reputation rests surely on the short stories), The Murder of Roger Ackroyd and The Nine Tailors, for instance? Most “Golden Age” authors cottoned on and created at least one recurring sleuth. Indeed, there’s something about the series that fits the mystery genre like a (Borgia-style poisoned) glove. It probably goes back to Holmes: while each individual problem at issue is clearly important, we are not plunged into it alone, but with friends. It has to be said that, as a lot of these writers were under pressure to churn out several books a year, quality could vary – I’m looking at you Mr Dickson Carr – yet this didn’t necessarily have to be the case.

Take a bow Arthur Ernest Ashley, aka Francis Vivian. For biographical information I refer you to Curtis Evans’s excellent introduction to the DSP editions, but one thing he didn’t look at was the way the Inspector Gordon Knollis series as a whole hangs together and develops. As Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahloo realised a couple of decades later, a run of ten offers plenty of scope without inviting formulaic staleness to creep in. The Martin Beck books were written over a decade and all but the first of the Knollis books were published between 1947 and 1956. The great Swedish writers explicitly wrote a series with a declared aim of documenting changes to Swedish society; whereas my feeling is that the way the Knollis books interlock is less by design and more a function of the author’s sheer craftsmanship. Yet here too we have a snapshot of a country on a cusp.

Take a bow Arthur Ernest Ashley, aka Francis Vivian. For biographical information I refer you to Curtis Evans’s excellent introduction to the DSP editions, but one thing he didn’t look at was the way the Inspector Gordon Knollis series as a whole hangs together and develops. As Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahloo realised a couple of decades later, a run of ten offers plenty of scope without inviting formulaic staleness to creep in. The Martin Beck books were written over a decade and all but the first of the Knollis books were published between 1947 and 1956. The great Swedish writers explicitly wrote a series with a declared aim of documenting changes to Swedish society; whereas my feeling is that the way the Knollis books interlock is less by design and more a function of the author’s sheer craftsmanship. Yet here too we have a snapshot of a country on a cusp.

I’ve had discussions about why some writers’ work remained in print whereas others’ didn’t. What Julian Symons called the "humdrum" writers have perhaps suffered most cruelly from the neglect of the ages, ironically so, given their influence on where crime writing was to go next; the modern “police procedural” surely owes a massive debt to Wills Crofts’s Inspector French, Simenon’s Maigret and their acolytes. Simenon remained in the firmament and Crofts wasn’t entirely eclipsed, yet nor did he shine on so crazily and most of the disciples faded like vanishing ink. The Knollis series is, I suppose, broadly in this lineage – no genius sleuth or moneyed adventurer, no country houses at which impossible crimes occur; indeed, few mystery novels are as fairly-clued. Knollis himself is lightly-sketched but feels very real and ages in real time; we’re told his hair is greying in book eight, whereas he’d been promoted from the provinces to Scotland Yard at the end of book one. Perhaps he should’ve kept an East Midlands pied à terre as he’s constantly being sent back there and solves no murders in the capital. This is one of the great fortes of the series: its sense of place.

I’ve had discussions about why some writers’ work remained in print whereas others’ didn’t. What Julian Symons called the "humdrum" writers have perhaps suffered most cruelly from the neglect of the ages, ironically so, given their influence on where crime writing was to go next; the modern “police procedural” surely owes a massive debt to Wills Crofts’s Inspector French, Simenon’s Maigret and their acolytes. Simenon remained in the firmament and Crofts wasn’t entirely eclipsed, yet nor did he shine on so crazily and most of the disciples faded like vanishing ink. The Knollis series is, I suppose, broadly in this lineage – no genius sleuth or moneyed adventurer, no country houses at which impossible crimes occur; indeed, few mystery novels are as fairly-clued. Knollis himself is lightly-sketched but feels very real and ages in real time; we’re told his hair is greying in book eight, whereas he’d been promoted from the provinces to Scotland Yard at the end of book one. Perhaps he should’ve kept an East Midlands pied à terre as he’s constantly being sent back there and solves no murders in the capital. This is one of the great fortes of the series: its sense of place.

The other, to me as I sit improbably in the early twenty-first century, is its rooting in its own time. One theory as to why Christie and Marsh, in particular, remained in print is that they’re light on period detail – only towards the end did much sense of “when” creep in. Poirot was past retirement age in the 1920s so it’s perhaps not surprising he struggled with the 1960s, as, one suspects, did other centenarians in that most youthful of decades. The Knollis books are subtly but firmly embedded in the 1940s and 1950s. Not in the same way as my favourite Miss Silver books, which are superb on the minutiae of life during rationing, the havoc wreaked on families – especially women – by WWII and its aftermath, but more subtly. These are accounts of a time when Britain was rebuilding both physically and mentally, beginning to look outwards at a mappa mundi no longer largely in the pink. Perhaps this is why they resonate so strongly now, when the polar opposite is taking place. Vivian is never heavy-handed or remotely polemical about this, indeed – with one notable exception to which we’ll come in the next paragraph – there’s little sense of what his political views might’ve been. He reports but rarely comments.

In fact, like Sjöwall and Wahloo, Vivian had a journalistic background and, while lacking the Swedes’ avowedly socio-political eye, there’s one issue that crops up repeatedly and with increasing urgency as the series draws to an end: there are mentions throughout of “another fiver for Teddy Jessop” (a tenner by the end of the series, there’s inflation for you). Jessop is presumably an allusion to Albert Pierrepoint, the UK’s official hangman during the period. Other fictional sleuths – Wimsey springs to mind – struggle with capital punishment but none so consistently and yet so matter-of-factly as Knollis. I expect someone has already written a learned thesis on the attitudes of early 20th century detective fiction to the death penalty but, reading long after its abolition in the UK, I’ve often noticed how in many stories the killer is allowed to “take the honourable way out” (if of sufficient social position), has a fatal accident trying to escape or the grisly result of the sleuth’s detections is glossed over if not ignored altogether. Not so here. Knollis declares an aversion to capital punishment on several occasions and is always aware of the shadow of the noose. A monkish friend called Brother Ignatius appears in the final two books to accentuate this, taking active steps towards Mr Jessop’s impoverishment.

In fact, like Sjöwall and Wahloo, Vivian had a journalistic background and, while lacking the Swedes’ avowedly socio-political eye, there’s one issue that crops up repeatedly and with increasing urgency as the series draws to an end: there are mentions throughout of “another fiver for Teddy Jessop” (a tenner by the end of the series, there’s inflation for you). Jessop is presumably an allusion to Albert Pierrepoint, the UK’s official hangman during the period. Other fictional sleuths – Wimsey springs to mind – struggle with capital punishment but none so consistently and yet so matter-of-factly as Knollis. I expect someone has already written a learned thesis on the attitudes of early 20th century detective fiction to the death penalty but, reading long after its abolition in the UK, I’ve often noticed how in many stories the killer is allowed to “take the honourable way out” (if of sufficient social position), has a fatal accident trying to escape or the grisly result of the sleuth’s detections is glossed over if not ignored altogether. Not so here. Knollis declares an aversion to capital punishment on several occasions and is always aware of the shadow of the noose. A monkish friend called Brother Ignatius appears in the final two books to accentuate this, taking active steps towards Mr Jessop’s impoverishment.

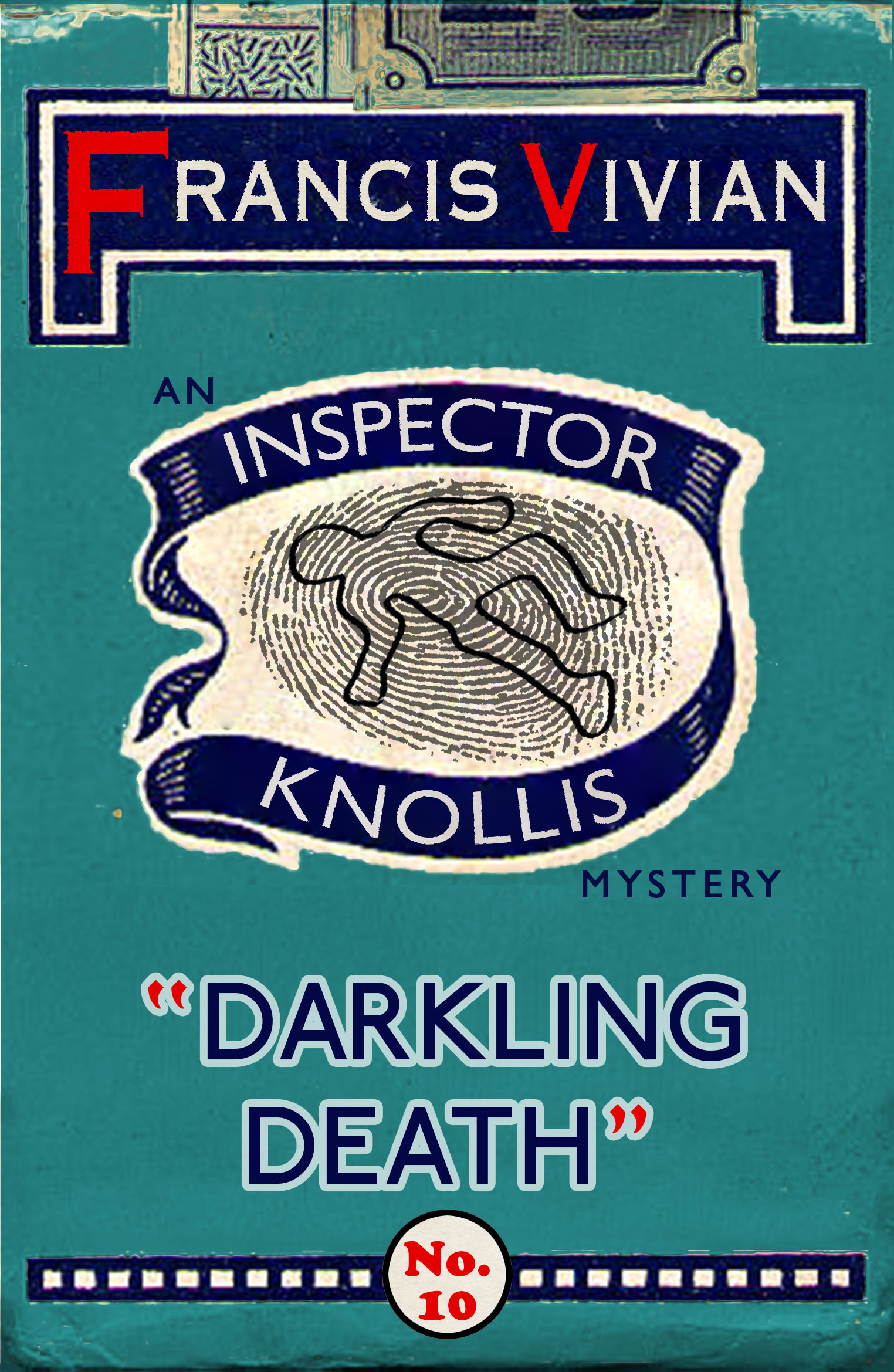

As this piece is about the series, I don’t want to single out individual books... which, as any astute reader will realise, means I’m about to do just that. There is no let-up in standards throughout the ten books but the one with the most obvious appeal to new readers and thus a good starting-point (it was my own) is The Singing Masons. Apiculture was among Vivian’s interests and he uses his knowledge to great effect, without ever getting overly technical. Curtis’s introduction homed in infallibly on the bees as a USP and he’s right; if you’re looking for one book to convert you to Vivian that’s the one I’d recommend, though I urge you to read all ten. I’d also like to mention the last, Darkling Death, an extraordinary little book. There’s a suggestion of an author wearying of the form in its elegiac quality, and yet it’s superb in its concision and crepuscularity. In some way I couldn’t justify for the life of me, the latter aspect reminded me a little of T.F. Powys’s Mr Weston’s Good Wine. In the previous nine books the first few chapters largely give us the set-up, after which we follow Knollis as he unravels the plot. Here he’s only really a supporting character and the crime feels almost incidental – you’ll know what I mean once you’ve read it. It also has some lovely digressions – all short and light of touch – such as a wonderful passage (on p.39 of the DSP edition) about why writers write. My antenna also twitched on a page where both the Toc H Lamp and the piper at the gates of dawn from The Wind in the Willows are mentioned. Could Syd Barrett have been a Knollis fan? Probably not, yet the first Pink Floyd album is entitled The Piper at the Gates of Dawn and features an instrumental called Pow R Toc H. This may not sound like the kind of thing you want from the last novel in a great mystery series and yet somehow it’s the – or a – perfect ending.

Vivian published a number of books outside the Knollis series, most of them before it. In his final novel, Dead Opposite the Church (which the DSP have also reprinted) Knollis is referred to in passing, adding to the sense of a world created. I’d dearly love to see the rest of the Vivian oeuvre reprinted, as original copies never seem to come up for sale and I wouldn’t be able to afford them if they did. I want to read them.

If, like me, you’re constantly on the lookout for a previously-unread mystery series to savour, I can recommend none more enthusiastically. Gordon Knollis may not be as flashy as some of his more celebrated confrères but this is among the most satisfying series I’ve ever read.

----------------------------

Nick Halliwell

Nick Halliwell runs Occultation Recordings but also writes about Golden Age crime