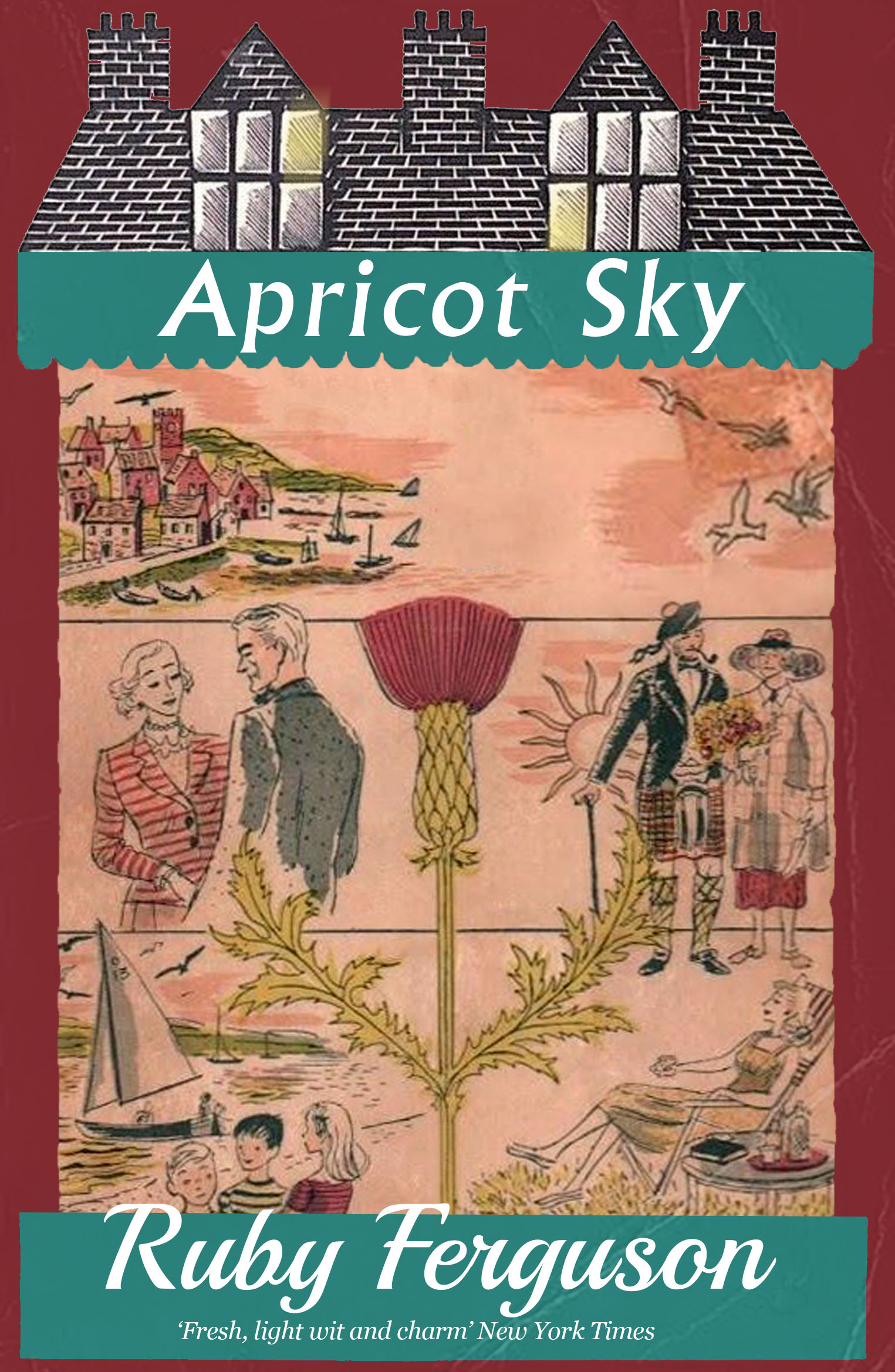

‘Thinness’: Metaphysics, Religion and Magic in Ruby Ferguson’s ‘Apricot Sky’

Published on: 20th July 2021

There is a term used to describe such places as the island of Iona, off Mull, on the West Coast of Scotland, where the transcendent and material worlds come so close they are barely separate; the word is ‘thin’. Anyone who has visited such a place will have felt it. It is both holy and magical, tug against one another though those discrete metaphysics, religion and magic, may seem to.

There is a term used to describe such places as the island of Iona, off Mull, on the West Coast of Scotland, where the transcendent and material worlds come so close they are barely separate; the word is ‘thin’. Anyone who has visited such a place will have felt it. It is both holy and magical, tug against one another though those discrete metaphysics, religion and magic, may seem to.

The Celtic world has no exclusive proprietary rights to the easy reach from material to unembodied, but the Celtic lands – and, it cannot be denied, their weather – seem, to anyone at all susceptible, to express and to shimmer with connections unspoken, unutterable.

In Apricot Sky Ruby Ferguson conveys, with a pleasurably fluctuating charge, this sense of ‘thinness’, both psychological and numinous. Which is not to say that the novel is, in any conventional sense, at all thin. It is not short, and it is packed with delectable and highly detailed accounts of the planning, procurement, preparation and presentation of food, as well as of eating it. Written at a time when rationing and coupons yet pertained, the book caters for many kinds of innocent greediness, from that of growing children to that of a courting couple fresh from the hill.

The set-up is from the first page hospitable to the reader, unless their prejudice be stern against the kind of Caledonian bourgeoisie who have domestic help (we are just post-War). The sense of being to a degree ‘out of time’ arrives swiftly with us, as we meet devoted gardener, wife, mother and grandmother, Mrs MacAlvey, in her drawing room, waiting for her daughter Cleo, lately back from America, due this very day to complete her complicated journey back to the family home, Kilchro House, in Scotland’s isle-tangled West.

In the household are Cleo’s younger, newly-engaged sister Raine, Gavin, Primrose and Archie, the three children of one of Mrs MacAlvey’s sons killed in war, a highly beguiling companionate not quite servant, Vannah Paige, ‘thin, brown, weather beaten’ keen fly-fisherman Mr MacAlvey, and staff.

More children are to arrive, usefully stuck-up and namby-pamby so that they may learn lessons as to rigidity and magic, hierarchy and freeness, in a signally practical yet metaphysical way, relating to a boat, a cave, and an island named Eil-oran inhabited by fairies, in whom all the MacAlvey family believe. There is a pleasingly horrific daughter-in-law Trina, wife of the War-spared son James. We shall also meet relaxed and decent Ian Garvine, engaged to Raine, and Neil, his cruelly handsome, almost silent, older brother, with whom Cleo is in, she believes, hopeless love.

A pretentious Scotch-mist author, Alistair Trossach (not his real name) has a prophylactic walk-on part early on, ensuring that we know that Ruby Ferguson herself knows with what old chestnuts she is flirting, and skirting, in this novel. An egotistical hypochondriac visits from England, deploying a not-that-recent operation to ensure her whim of steel be served, and referring to her, physician, spouse as ‘Doctor’. The book is often slyly funny.

Amid this comedy of risible ambulatory types live those we come to favour as we read on, each of whom is identifiably able to love or to care. This brings them into the rounded fictional dimension where we see things from their point of view, with one important exception that is at the very end resolved with something like magic, in which you will or will not believe.

Ian’s older brother Neil is referred to by some as ‘the Larrich’, which is the name of the Garvine family home. Scots gentry nomenclature is a joy and a mystery, maybe even to those who understand it. [When the obituaries of the late Lord Macpherson appeared, he was in the Scots papers referred to as ‘Cluny’, for he was the clan chieftain of the Macphersons and thus took the name of his ancient abode; this occurs, though not invariably, at all levels of Scots society; I knew a fisherman who died young whose name on his gravestone reads simply ‘Seaview’.] That the connection between soul and place goes very deep is one of the, lightly-worn, ‘thin’ themes of Apricot Sky.

The story we are given spans a summer, which has an end in sight, the wedding of Raine and Ian, and the return to boarding school of Gavin, Primrose and Archie and the snobbish, fusspot, London children Cecil and Elinore. The wedding is to take place on the eleventh of September, a date upon which other things have happened than what arrests it unmercifully in our minds now. So sufficient in the supernatural and shivery is this book in itself that one need not import extrinsic and occluding coincidences of what Martin Amis calls ‘event-glamour’.

By the time we reach the surprising and unsurprising, hurtling yet also dreamlike and silvery, conclusion of the story, Ruby Ferguson has had her way with us, making us believe several impossible, many charmingly improbable, things, not least a sexy siren from central casting, magically rendered harmless at the last by a move that is indeed a checkmating, and a vagabond faerie child by the-hidden-in plain-sight name of Gull, who is something quite else in the quotidian realm.

By the time we reach the surprising and unsurprising, hurtling yet also dreamlike and silvery, conclusion of the story, Ruby Ferguson has had her way with us, making us believe several impossible, many charmingly improbable, things, not least a sexy siren from central casting, magically rendered harmless at the last by a move that is indeed a checkmating, and a vagabond faerie child by the-hidden-in plain-sight name of Gull, who is something quite else in the quotidian realm.

How has Ruby Ferguson done it?

I believe she may have written a ballad in prose; the ‘refrains’ are singingly chromatic accounts, most often of weather, land or sea, passages that name colours successively within runs of description that do not bore, taken from the life as they are; it’s something like watching tweed being made, the bright threads combining to offer veracity to nature. She lays colour down with plein-air freshness and sincerity.

The novel is a Highland lay, a Carmen Gadelicum, offering spells cast and loves lost and found, as opposed to the Border Ballad economies of revenge and punishment (for the echo of those we must turn to the novels of Muriel Spark, also ‘thin’, and with inestimably more place for the Almighty).

Apricot Sky derives energy and conviction from the fiction of genre, without resort to plot by rote, laziness or cynicism. It is remarkable that a book so rich in types should yet engage and surprise; I would ascribe this to Ruby Ferguson’s capacity to keep the supernatural and the unsaid in play even when she is at her most material or talkative.

It is a novel that deals, in the fashionable term, with the liminal, with childhood and with adolescence (this is particularly well shaded-in; watch for Primrose’s use of language and her bookishness), with the time before the time now, with states of love and with the otherness of others, with loneliness and aloneness and the difference between them. That there is a good deal of tart comedy at the expense of Ruby Ferguson’s smugger creatures adds to the ballad-like concretion of this paradoxical novel.

The romantic climax of the tale comes almost incidentally, perhaps implausibly (but doesn’t romantic love, don’t life-altering moments, feel like that?) and is as real or as unreal as you wish to believe footsteps left in the dew may be.

She has completed her song out of the West and worked her spell upon the reader, who may well be moved to shake themselves, return to the beginning, and – this time – to try to make a map. The village, mountains, big houses, castles, and the little islands where she set her tale may be mappable; the lighter airs playing above, less so. But Ruby Ferguson has forecast and scored them in.

She has risen to her epigraph, taken from Robert Louis Stevenson, and recreated one recipe for heather ale and its intoxications in the form of Apricot Sky.

© 2021 Candia McWilliam. Excerpted from the introduction to Apricot Sky (Dean Street Press, 2021) by Ruby Ferguson.