Blitz Spirit with Lucy Worsley: a Timely Revision of Britain in Crisis

Published on: 25th February 2021

During WWII, German planes dropped 32,000 tonnes of bombs on British cities, an eighth-month-long assault known as the Blitz. It is a period well known to us – not only familiar ground in most school history lessons but recent enough that many who experienced it are still alive today. And yet, how much of what we ‘know’ is true? This is the question that Lucy Worsley sets out to answer in Blitz Spirit, a documentary that peels back the myth of the unshakeable British morale.

Advances in military technology in the lead up to WWII brought new threats to civilian life. Unlike WWI, this was a war that was going to be fought at home. The British government feared widespread panic just as much as any enemy troops; a collapse in morale could cost Britain a victory and so, as Worsley explains, any chance of winning ‘depended on the ordinary people of Britain keeping their nerve’. The Civil Defence Service did just that, preparing civilians to protect themselves and their communities. Pouring through archives, Worsley uses diaries and memoirs of those who signed up to reconstruct a true story of the Blitz, warts and all. The characters she follows come from all walks of life, from a teenage shop girl to a socialite, and between them they offer an intimate cross-section of British society at a time of crisis.

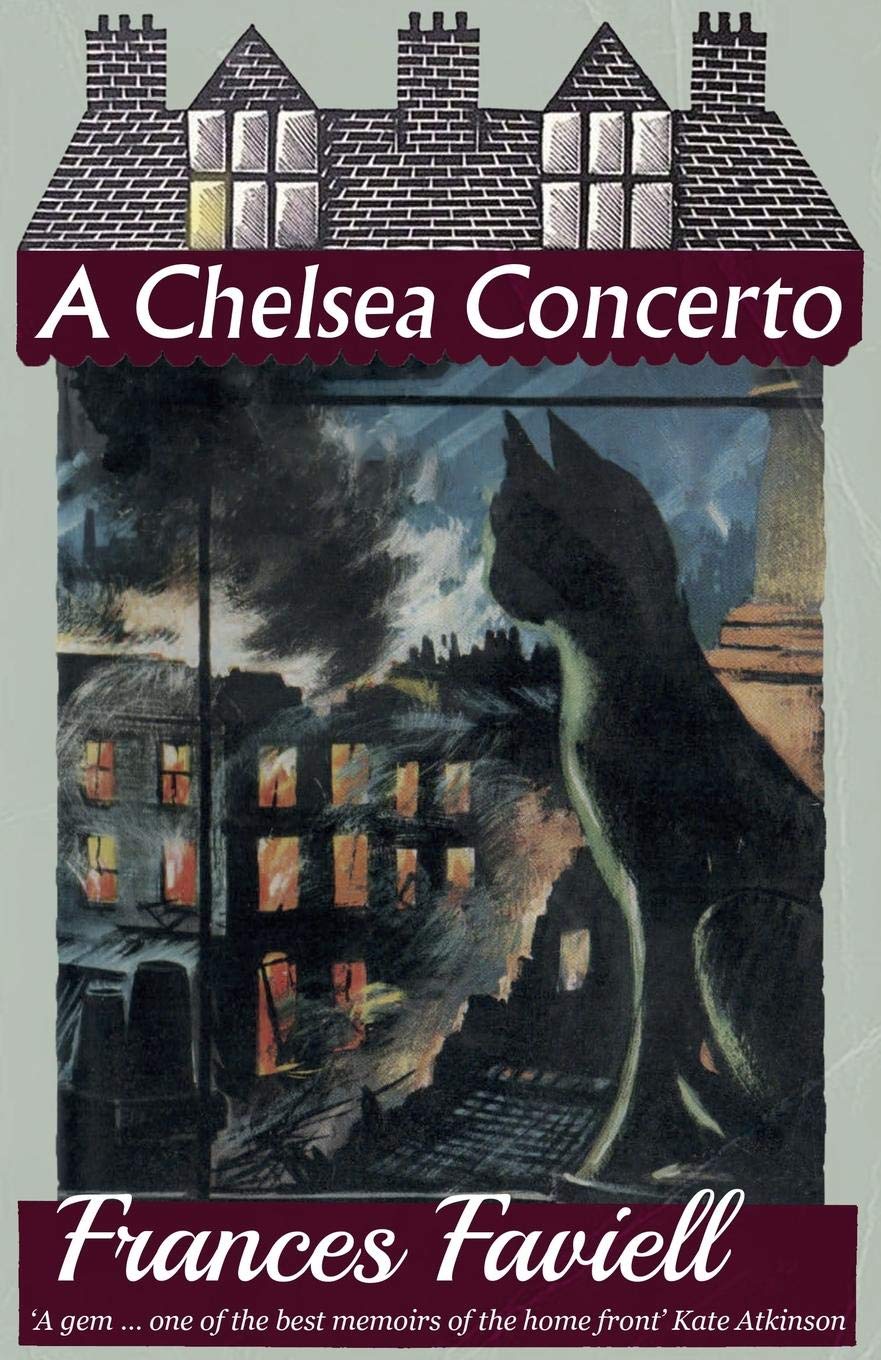

One of these central characters is Frances Faviell (played by Rhiannon Neads), artist and author of several novels and a Blitz memoir, A Chelsea Concerto (1959) – the latter forming the basis for her narrative. She is introduced as the picture of elegance, depicted sitting among her paintings and sipping a pink cocktail. ‘It seemed extraordinary that one could listen over the air on a perfect summer day to such world-shaking events,’ she confesses, describing the declaration of war in 1939. Indeed, it seems incongruous to imagine that she will soon don a nurse’s uniform and join over a million other volunteers as part of the Civil Defence Service.

One of these central characters is Frances Faviell (played by Rhiannon Neads), artist and author of several novels and a Blitz memoir, A Chelsea Concerto (1959) – the latter forming the basis for her narrative. She is introduced as the picture of elegance, depicted sitting among her paintings and sipping a pink cocktail. ‘It seemed extraordinary that one could listen over the air on a perfect summer day to such world-shaking events,’ she confesses, describing the declaration of war in 1939. Indeed, it seems incongruous to imagine that she will soon don a nurse’s uniform and join over a million other volunteers as part of the Civil Defence Service.

Worsley reminds us from the outset that ‘Blitz Spirit’ is a complicated idea. Her characters’ diaries reveal that emotions were mixed, ranging from excitement (17-year-old Nina hopes for a ‘release from the dull predictability of life’) and giggles during Civil Defence training, to apathy when, six months into the war, the threat of air raids hasn’t materialised. Frank Hurd, a London fireman, confesses to being ‘fed up’ with the monotony of false alarms. People grumble that full-time Civil Defence workers are a waste of public money. These candid accounts begin to chip away at the jovial stoicism of the Blitz Spirit myth, exposing the difficulties of talking about any ‘public mood’ as if it were a monolithic and unchanging thing.

But then the real terror arrives, and Worsley doesn’t hold back. The first night of the Blitz, 7th September 1940, is recounted in minute detail, snippets of diaries read out in a montage of escalating panic. Descriptions of the bombing that shook the East London docks that night are not for the faint-hearted. Our diarists write of a ‘sheet of flame’, an ‘inferno’, of finding bits of bodies amid the wreckage of houses. Worsley tells us that ‘the bombs [were] so powerful that even at a distance they could kill you by sucking the air out of your lungs’. While the newspapers – prevented from publishing Blitz photographs or death statistics by a 28-day embargo – reported that ‘there is no reason whatsoever for dejection or depression’, Worsley blows apart this sanitized fiction, giving us not just dejection and depression but panic, hysteria and chaos.

Most traumatic is a dramatized scene from Frances’s memoir. Walking home from her nightshift, she hears the cries of someone trapped beneath a collapsed house – ‘like an animal caught in a trap’. Determined to help, Frances is stripped down to her underwear and lowered into the wreckage by two rescue workers, torch between her teeth. Finding only ‘one great, gaping red mess’ where a man should be, there is nothing she can do but hold a chloroform-soaked hanky over his mouth until his crying stops. Moments like this, retold with extraordinary sensitivity, remind us that the Blitz was a warzone, as terrifying and dangerous as those across the channel.

Worsley pauses frequently to comment on the social tension that such destruction caused. While poor Londoners fought for space to shelter in underground stations, those who could afford it could pay for bed and breakfast in the Savoy Hotel basement. Writing in her diary, Nina describes one East London shelter as a ‘hell-hole’ with ‘people sleeping on piles of rubbish’. When the press and propaganda boasted that Britain ‘can take it’, it was working class people living near heavily targeted factories and docklands, and without adequate shelter, who bore the brunt of the damage. We must, Worsley tells us, acknowledge the government failings that left thousands of people homeless, hungry and vulnerable. Community initiatives stepped up to fill the gap, providing food, clothing and shelter to those in need. Worsley cautions, ‘if this sense of resourcefulness and resilience is what we call Blitz Spirit, I think we need to remember it was born entirely out of necessity’.

(Left: Lucy Worsley with examples of the iconic 'Keep Calm and Carry On' progaganda poster. Right: actress Rhiannon Neads, who plays the role of A Chelsea Concerto author Frances Faviell).

Her words strike a chord. For though Blitz Spirit does a wonderful job of transporting us back to the 1940s, the real star of the documentary is the subtle editing, interspersing archival footage with shots of contemporary London. Never confronted explicitly, the Covid-19 crisis is a haunting undercurrent. Worsley describes how the nightly air raids quickly became ‘the new normal’; the familiar phrase does the legwork, reminding us that we are not the first to have had our daily lives disrupted. There are obvious material differences between the Blitz and now (shots of Londoners crowding into tube stations feel intensely alien), but the parallel teaches us an important lesson: ‘history is inherently messy business’. We wouldn’t want textbooks to airbrush the spectrum of fear, frustration, division, excitement, fun and fury out of our lockdown experience, and we owe it to those who lived through the Blitz to unpick the reality behind the myth.

Florence Ward

Twitter: @FlorenceM_W

www.florence-ward.com