Do Not Keep Calm and Carry On

Published on: 16th April 2020

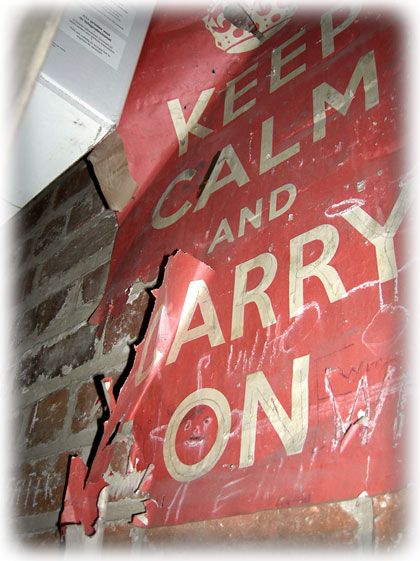

We are living in difficult times. In the face of the global coronavirus pandemic, our everyday lives have been unimaginably disrupted. Over the last few weeks, comparisons between our current situation and that of those living through the Blitz have floated around the media. Understandably, this parallel can sometimes seem reductive. “Blitz Spirit” — though intended as inspirational shorthand for the way people manage during times of crisis — has often been condensed into a convenient myth of universal stoicism and good cheer. Wartime propaganda has bolstered this myth, with the well-known order to Keep Calm and Carry On despite the circumstances giving an impression of the Blitz as something that was simply endured with the characteristically British stiff-upper-lip.

We are living in difficult times. In the face of the global coronavirus pandemic, our everyday lives have been unimaginably disrupted. Over the last few weeks, comparisons between our current situation and that of those living through the Blitz have floated around the media. Understandably, this parallel can sometimes seem reductive. “Blitz Spirit” — though intended as inspirational shorthand for the way people manage during times of crisis — has often been condensed into a convenient myth of universal stoicism and good cheer. Wartime propaganda has bolstered this myth, with the well-known order to Keep Calm and Carry On despite the circumstances giving an impression of the Blitz as something that was simply endured with the characteristically British stiff-upper-lip.

This is only half the story. Despite its fame — and the plethora of mugs, T-shirts, tote bags, badges and other gift items bearing the slogan — Keep Calm and Carry On was rarely publicly displayed during the war and remained unknown until the poster was rediscovered in a bookshop in 2000. It is less of a reflection of the stoic behaviour of those who lived through the Blitz, rather yet another example of looking at the past through rose-tinted lenses. No wonder the parallel feels cruel: as we are all now realising, it is impossible to carry on as normal when our world has been turned upside down, and nor should we.

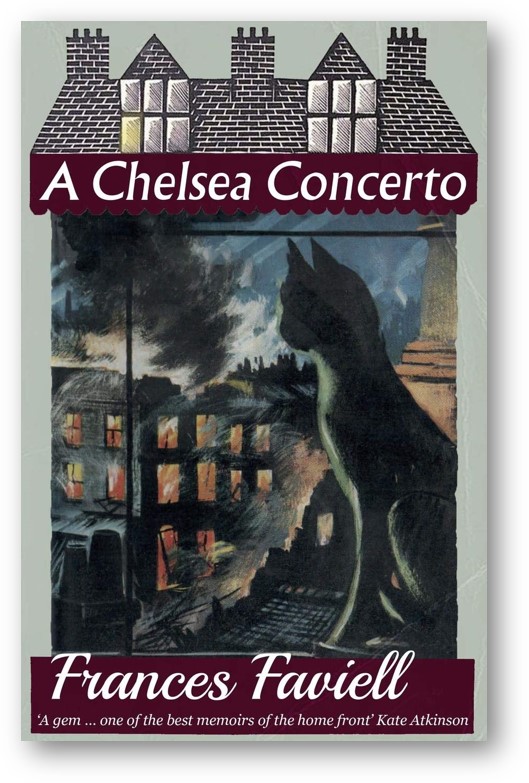

Blitz literature can offer a much more meaningful insight into the lives of those who experienced the crisis first-hand, and Frances Faviell’s  memoir of volunteering for the Red Cross during the Blitz, A Chelsea Concerto (1959), peels away the surface of the myth to expose its subtle reality. From 7th September 1940 to 11th May 1941, over 43,500 civilians were killed by bombs dropped on towns and cities across the UK (source: IWM). Those who lived through it did not simply remain calm and carry on as normal. Everyday lives were disrupted as people were forced to negotiate curfews, blackouts and air raids — 57 nights in a row, for Londoners from September to November 1940. Faviell describes disbelief, confusion, fear, anger and trauma. After the first raid on London, she ‘felt fury – a wild anger of which I did not know I was capable. I found I was shivering with some kind of emotion hitherto unknown to me’. The victims of the Blitz do not all bear the bombings with stiff-upper-lipped stoicism; they are often understandably ‘panic-stricken’, ‘hysterical’ and ‘frantic’. Fights break out in air raid shelters. There is outrage at the government’s scant promise of £7 10s toward a funeral if a volunteer is killed on duty. Faviell confesses that she ‘often rebelled violently’ against the Florence Nightingale role, not wanting to set foot in another hospital. Countless other wardens that she talks to share this anxiety; they are all ‘bloody scared’.

memoir of volunteering for the Red Cross during the Blitz, A Chelsea Concerto (1959), peels away the surface of the myth to expose its subtle reality. From 7th September 1940 to 11th May 1941, over 43,500 civilians were killed by bombs dropped on towns and cities across the UK (source: IWM). Those who lived through it did not simply remain calm and carry on as normal. Everyday lives were disrupted as people were forced to negotiate curfews, blackouts and air raids — 57 nights in a row, for Londoners from September to November 1940. Faviell describes disbelief, confusion, fear, anger and trauma. After the first raid on London, she ‘felt fury – a wild anger of which I did not know I was capable. I found I was shivering with some kind of emotion hitherto unknown to me’. The victims of the Blitz do not all bear the bombings with stiff-upper-lipped stoicism; they are often understandably ‘panic-stricken’, ‘hysterical’ and ‘frantic’. Fights break out in air raid shelters. There is outrage at the government’s scant promise of £7 10s toward a funeral if a volunteer is killed on duty. Faviell confesses that she ‘often rebelled violently’ against the Florence Nightingale role, not wanting to set foot in another hospital. Countless other wardens that she talks to share this anxiety; they are all ‘bloody scared’.

But as well as being a gruesome glimpse into the harsh reality of the Blitz, Faviell’s memoir is a source of hope and inspiration. Her account is full of moments of community and astounding bravery, often brushed off as ‘’S all in the day’s work’. Faviell writes that:

The Blitz was providing something besides bombs. It was making people talk to one another. People in shops, in the buses, in the streets often talked to me now. They opened up amazingly about how they thought and what they thought – how they felt and what they felt. They all liked to see the nurses’ uniforms – and were loud in their praise of the nurses, the firemen, and the wardens.

Airbrushing these moments of community support, stoicism and bravery into a propaganda slogan overlooks exactly the strength it would have taken to execute them. The stories in Faviell’s account are all the more meaningful for their contextualisation within the horrors of the wider period.

Reading A Chelsea Concerto, it’s hard not to notice similarities to the crisis we are now dealing with. Yes, we are living through a fundamentally different time; our own crisis is not, as Faviell describes, breaking down class barriers, but perhaps heightening them. This makes the need for mutual aid even greater. And though we cannot come together in person, we have done so remotely, with communities galvanising support via social media. Like those living through the Blitz, we are also confused, angry, scared and, at points, disbelieving. But we have also supported one another in the ways that we can, through food deliveries and video calls.

.jpg) If there is a comparison to be made between the so-called “Blitz Spirit” and the way we have responded to the COVID-19 crisis, it is in the sense of community that has emerged from the crisis. In spite of the symbolic invocation, Britain during WWII did not just keep calm and carry on as normal; the fabric of society shifted, ultimately leading to the creation of the Welfare State that we are now relying on so heavily. As Faviell’s memoir beautifully and painfully reveals, the “Blitz Spirit” was about moments of stoicism but, more importantly, compassion and a recognition of the need to look after one another. These will be difficult times, but we can get through them together.

If there is a comparison to be made between the so-called “Blitz Spirit” and the way we have responded to the COVID-19 crisis, it is in the sense of community that has emerged from the crisis. In spite of the symbolic invocation, Britain during WWII did not just keep calm and carry on as normal; the fabric of society shifted, ultimately leading to the creation of the Welfare State that we are now relying on so heavily. As Faviell’s memoir beautifully and painfully reveals, the “Blitz Spirit” was about moments of stoicism but, more importantly, compassion and a recognition of the need to look after one another. These will be difficult times, but we can get through them together.

Florence Ward

Twitter: @FlorenceM_W