The Anthromorphic ’Thirties

Published on: 18th November 2019

.png) Anthromorphism (the attribution of human characteristic to animals or objects) has been around forever, yet it was in the 1930s—with its Great Depression need for whimsy – that this bizarre predilection peaked. As Dean Street Press publishes so many titles that date from The Thirties, it’s no surprise that anthromorphism is one of our (many) guilty pleasures. No moral incertitude seemed to have existed when putting a hopeful face on a potato alongside a recipe for french fries, and there was certainly no shortage of cannibalistic pigs brandishing plates of bacon with a “come and get it!” glee. This was the era of talking mice and obstreperous ducks, and to paraphrase one of the decade’s most famous songs, when it came to anthromorphatic crap, “anything went”.

Anthromorphism (the attribution of human characteristic to animals or objects) has been around forever, yet it was in the 1930s—with its Great Depression need for whimsy – that this bizarre predilection peaked. As Dean Street Press publishes so many titles that date from The Thirties, it’s no surprise that anthromorphism is one of our (many) guilty pleasures. No moral incertitude seemed to have existed when putting a hopeful face on a potato alongside a recipe for french fries, and there was certainly no shortage of cannibalistic pigs brandishing plates of bacon with a “come and get it!” glee. This was the era of talking mice and obstreperous ducks, and to paraphrase one of the decade’s most famous songs, when it came to anthromorphatic crap, “anything went”.

It seems impossible to have existed in the ’30s without being in possession of salt and pepper shakers in the form of lettuces in love, ad men jumping on this craze for ‘stuff that isn’t human acting human’, with a whole host of not-very-exciting brand mascots, most of which didn’t make it past Pearl Harbor (it was probably best that our Victory Gardens didn’t have beguiling smiles and cheerful personalities; it isn’t patriotic to eat one’s friends) appearing in The Great Depression.

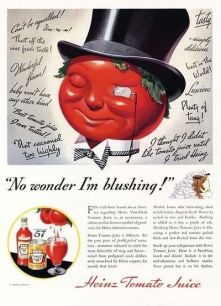

Planter’s ‘Mr. Peanut’ had been around since 1916, yet really came into his own in the glamour-hungry 1930s. Heinz seized this topper-wearing  “Puttin’ On The Ritz” chic beloved of the decade, but its ‘Mr. Tomato’ lacked the Fred Astaire finesse of the Planter’s mascot. Sure, he had the top hat, starched collar, and monocle, yet his facial expression gave him the appearance of one of those self-made captains of industry who’d show up in RKO pictures of the era and usually end up paying off a showgirl. ‘Mr. Tomato’ looked louche and self-serving, his chickens soon coming home to roost in the form of a lawyer masquerading as a bell hop serving him divorce papers. (No wonder he’s blushing).

“Puttin’ On The Ritz” chic beloved of the decade, but its ‘Mr. Tomato’ lacked the Fred Astaire finesse of the Planter’s mascot. Sure, he had the top hat, starched collar, and monocle, yet his facial expression gave him the appearance of one of those self-made captains of industry who’d show up in RKO pictures of the era and usually end up paying off a showgirl. ‘Mr. Tomato’ looked louche and self-serving, his chickens soon coming home to roost in the form of a lawyer masquerading as a bell hop serving him divorce papers. (No wonder he’s blushing).

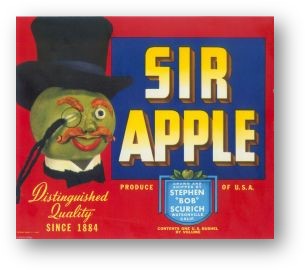

In saying that, he probably fared better than the bizarre ‘Sir Apple’; certainly, he was as dapper as the other monocled mutineers of a decade  obsessed with how the other half lived. He even came with a title. Unfortunately, he didn’t come with two eyes, and one can only guess as to why the commercial artist charged with creating ‘Sir Apple’ gave him a jaunty monocle positioned over…no eye. One suspects that if anyone at Sir Apple HQ noticed this anatomical anomaly, it must have seemed understandably trivial against a backdrop of Bread Lines, Dust Bowls, and European fascism. “Nobody’s gonna notice”. Eighty years later, we’re still noticing.

obsessed with how the other half lived. He even came with a title. Unfortunately, he didn’t come with two eyes, and one can only guess as to why the commercial artist charged with creating ‘Sir Apple’ gave him a jaunty monocle positioned over…no eye. One suspects that if anyone at Sir Apple HQ noticed this anatomical anomaly, it must have seemed understandably trivial against a backdrop of Bread Lines, Dust Bowls, and European fascism. “Nobody’s gonna notice”. Eighty years later, we’re still noticing.

Of course, anthromorphism was a gift to the lazy copywriter tasked with cutesy greeting card sentiments. In a decade that gave us the glittering word play of Bringing Up Baby and It Happened One Night, it is oddly dichotomous that the ’30s also adored the cringy, uninspired, and utterly unfunny pun. I am sure that it started with the artwork, and one can only imagine the apathetic and eye-rolling approach taken by a writer when a pair of smitten carrots looking longingly at each other was placed upon his desk. “Could you CARROT all about me, Valentine?” can’t have been copy of which anyone was proud, but it kept the writer out of Hooverville, and paid for that next Sears Roebuck catalogue installment.

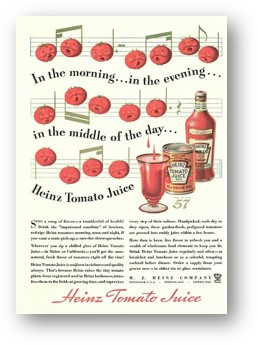

Returning to Heinz (determined to make anthromorphistic advertising work for them), the brand scored a spectacular double coup with musical notes that are also tomatoes that are also singing faces! But why did they stop there? Why not go for reverse anthromorphism and fashion the staves to look like veins pulled from a human leg?

Returning to Heinz (determined to make anthromorphistic advertising work for them), the brand scored a spectacular double coup with musical notes that are also tomatoes that are also singing faces! But why did they stop there? Why not go for reverse anthromorphism and fashion the staves to look like veins pulled from a human leg?

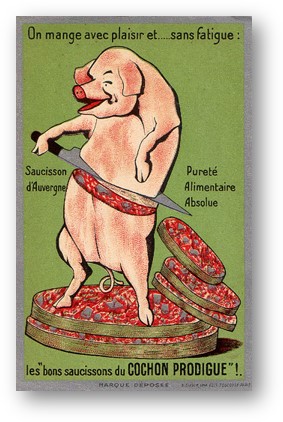

Grotesque? Oh, you ain’t seen nothin’ until you view the ‘you-can-never-unsee-it’ French ad’ for sausages depicting a pig, gripped with  deranged laughter, as he slices meat from his own torso (didn’t a man in Germany recently advertise on the internet for somebody to do this to him?) It is a particularly gruesome image, and had it ever been turned into an animated feature, there is no doubt in my mind that Peter Lorre would have voiced it.

deranged laughter, as he slices meat from his own torso (didn’t a man in Germany recently advertise on the internet for somebody to do this to him?) It is a particularly gruesome image, and had it ever been turned into an animated feature, there is no doubt in my mind that Peter Lorre would have voiced it.

Clearly, the phenomenal success of Walt Disney had much to do with the anthromorphic ’30s; Mickey Mouse debuted in 1928, just in time for him and his farmyard friends to capture Depression Era hearts. What one forgets today is just how popular Mickey and Co. were with adults of the ’30s; they were fun, optimistic, whimsical, and cute – a genuine diversion from the real life anxieties of such difficult times.

Anthromorphism is still with us (the Geico Gecko probably the most famous in terms of advertising, and Mr. Whippy, that 1950s’ mascot with his lovely, Rococo-style ice-cream wig, is still around), but unless one is a collector of such junk (and there are many collectors of such junk; I myself resist the urge on an almost daily basis), most adults no longer want teapots that smile at them, or toilet-roll holders that look like potatoes that also have faces with mustaches. And perhaps this speaks to the fact that – although we tend to think we’re living through ‘the worst of times’ – compared to the 1930s, we just might be living through the best of ’em.

Amanda Hallay